Black Maternal Health Week Through the Eyes of Black Physicians

We asked four Black women physician advocates from our LTA 2025 cohort to reflect on Black Maternal Health Week.

BLACK MATERNAL HEALTH WEEK

For years, Physicians for Reproductive Health (PRH) has joined the Black Mamas Matter Alliance in celebration of Black Maternal Health Week (BMHW), a week-long campaign from April 11th-17th, dedicated to spreading awareness, promoting intersectional activism, and prioritizing community-building to amplify the voices, perspectives and lived experiences of Black Mamas and birthing people.

For decades, Black birthing people have borne the brunt of adverse maternal health outcomes catalyzed by systemic racism, medicalized violence, and limitations in access to full-spectrum reproductive health care. As the cost-of-living increases, protections for abortion care, gender-affirming care, and providers of that care are decreasing, our sense of safety is shifting, and we are witnessing and experiencing widening gaps in health disparities that have the greatest impact on the most marginalized members of our community.

Following the 2022 Dobbs’ decision, resulting in the overturning of Roe v. Wade, we are seeing these trends escalate in real-time, as Black birthing people are three to four times more likely to experience maternal mortality than their white counterparts (KFF, 2024), are more likely to experience gaps in adequate health insurance, as well as limited access to safe, affordable housing, and healthy, nutritious foods. This intersectional public health crisis is on the rise as we are seeing funding pulled from programs that keep many BIPOC families alive and well. In these moments, it can be hard to feel hopeful. Yet we remain certain that a breakthrough is on the rise. You may ask how do we do it? Let me break it down for you.

This year is not just about spreading awareness, as these trends were prevalent long before 2025. This year is about honoring the work and dedication of our community by way of the BMHW’s 2025 theme: “Healing Legacies: Strengthening Black Maternal Health Through Collective Action and Advocacy.” Black people are no strangers to adversity and come from a long legacy of alternative approaches to care, wellness, healing and most importantly, safety. We have kept and will continue to keep each other safe. We have come a long way since 12 Black women came together in 1994, to coin the term Reproductive Justice, and as we honor their legacy, it is just as important to honor the hard work, dedication, and power of Black-led perinatal, maternal, and reproductive health organizations and providers committed to driving systemic change and fostering community healing.

Now, how does PRH come into play in this? Well, PRH is led by the incredible Dr. Jamila Perritt, an ob/gyn in DC and an alum of the Leadership Training Academy aka LTA. Every year, LTA selects around 30 physician advocates with the intention of cultivating and supporting emerging leaders in reproductive and sexual health advocacy, with a specific focus on advocacy related to abortion.

Maura Jones Pullins

Keri Garel

Joi Spaulding

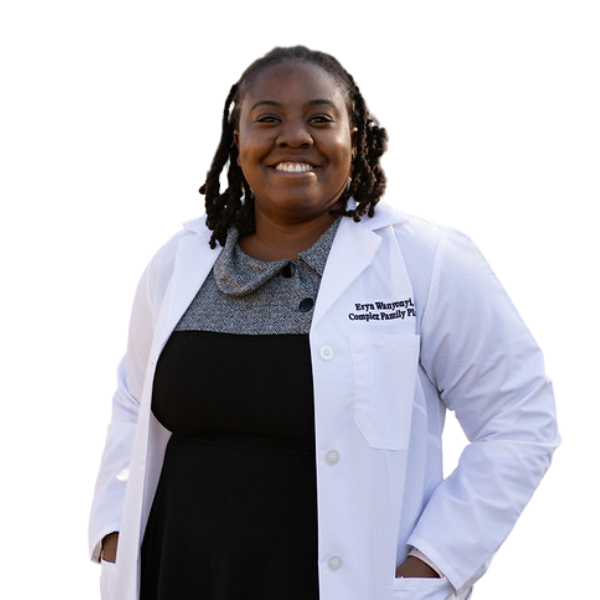

Eryn Wanyonyi

To honor this year’s theme, we asked four Black women physician advocates from our LTA 2025 cohort to reflect on what Black Maternal Health Week means to them personally and professionally, the connection between systemic racism, reproductive policy, and maternal health outcomes, and the emotional and intellectual labor that Black women physicians carry. Our goal was to deepen our understanding of the lived experience of Black women physicians in our community, while simultaneously calling in what many people might lose sight of as we continue to struggle for liberation under the current sociopolitical landscape.

I had the chance to interview the following physicians from PRH’s LTA 2025 Class:

- Keri Garel, ob/gyn in Massachusetts

- Joi Spaulding, family medicine physician in North Carolina

- Maura Jones Pullins, maternal fetal medicine physician in North Carolina

- Eryn Wanyonyi, ob/gyn in Illinois

What does Black Maternal Health Week mean to you—personally and professionally?

For Dr. Eryn Wanyonyi this Black Maternal Health Week is both sobering and an opportunity to demand equity and justice for our community.

“This week is so important. I am a Black woman. I take care of Black women. I have seen and experienced firsthand the disproportionate rates of maternal morbidity and mortality in Black birthing people. And it frightens me, both personally and professionally.”

She sees this week as a space for truth-telling: “This week is an opportunity to further amplify and bring awareness to the lived experiences of Black women so we can create sustainable, systemic change.”

Dr. Keri Garel emphasizes that the week is also about collective accountability and communal support that expands far beyond the birthing experience.

“Everyone wants their birth to be a safe and joyful experience. Black Maternal Health Week is a dedicated time for us to commit to making that desire a consistent reality for Black birthing people…But maternal health does not begin and end with birth,” she adds. “To live and parent in a safe, supportive environment requires long-term resources and efforts of an entire community.”

For Dr. Maura Jones Pullins, the week is a reminder of her purpose, detailing the devastating reality of our health care landscape.

“Personally, it’s a reminder that my presence in medicine isn’t just about representation—it’s about reformation. Professionally, it’s a call to action. The data is devastating. Behind every statistic, there is a story, and I carry many of those stories with me every day.”

Dr. Joi Spaulding uses the week to reflect on the “why” that grounds her work:

“It reinforces my commitment to advocating for equitable, compassionate, and culturally competent care for all Black birthing people.”

What would you say to people who underestimate the connection between systemic racism, reproductive policy, and maternal health outcomes?

Our Fellows kept it real, letting us know the deep history of medicalized racism and the implications that racism has on Black bodies today.

“Read a history book, open your eyes, turn on your television,” says Dr. Wanyonyi. “The consequences of systemic racism on reproductive healthcare and policy can be seen everywhere.”

She draws a clear connection between the present and the not-so-distant past: “The ‘father’ of gynecology built his success by experimenting on enslaved Black women and operated on the premise that they don’t experience the same pain as white people. Today, many Black birthing people do not receive adequate pain control in labor based on this same assumption.”

She adds, “Throughout history, we see birth control and sterilization being used to control Black bodies. This still happens. Abortion bans are killing Black women. Amber Nicole Thurman, Candi Millier, and Porsha Ngumezi should be alive today. Reproductive policy has long been rooted in racist ideals, and systemic racism contributes to the devastating maternal health outcomes that we see in Black birthing people.”

Dr. Garel unpacks the current disparity, emphasizing the variability in adequate health insurance access across the country:

“Medicaid covers more than four in ten births nationally, but coverage during and outside of pregnancy varies from state to state. States lacking expanded Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act also have wider racial and ethnic disparities in maternal health outcomes.”

“An in-hospital maternal care bundle for preeclampsia will only get us so far,” she warns, “when patients lack access to risk-reducing care before preeclampsia even begins.”

For Dr. Jones Pullins, the solution begins with reckoning.

“This is not about individual behavior or isolated events—it’s about structures. From discriminatory housing policies to biased clinical algorithms, systemic racism touches every part of a person’s life, including their pregnancy and postpartum experience.” “These connections aren’t hypothetical,” she says. “They are evidenced, generational, and deadly.”

As a Black woman in medicine, how do you navigate caring for Black birthing people while also holding your own identity and experiences?

Dr. Wanyonyi describes her experience as a layered, nuanced, and deeply personal responsibility.

“I identify with the fear of not being taken seriously. I identify with the joy that comes with seeing a doctor that looks like me. I also recognize the influence and position I hold as a physician. I understand the weight it holds when my patients are entrusting their care to me.”

“I show up, I listen, I share, I commiserate, and I advocate,” she says. “And I do it again and again. And I will for as long as I can.”

Dr. Garel adds,

“Hearing my Black patients say, ‘I’ve never had a Black OBGYN before!’ with surprise and joy fills me with validation, pride, and an added sense of duty.”

She reflects on the pressure of being one of few in predominantly white spaces: “The adage of being ‘twice as good to get half as far’ is rooted in truth. But the numbers make it clear—the status quo is killing Black women.”

Dr. Jones Pullins speaks to the connection between care and identity:

“I see my family, my friends, and myself in my patients—and that connection fuels me. Showing up fully—both as a physician and as a Black woman—is an act of advocacy in itself.”

Dr. Spaulding lifts the power of authenticity in her work:

“By being authentic with my patients, I hope to create a space where they feel comfortable doing the same… I recognize the privilege I have in being able to feel this way at my job, and I hope that by normalizing this, others will feel empowered to show up as their true selves too.”

What do you wish more people understood about the emotional and intellectual labor that Black women physicians carry—not just clinically, but socially and systemically?

Dr. Wanyonyi:

“The journey to become a Black physician has many challenges and obstacles. Throughout every step, there are people that doubt and question your intelligence and abilities because you are Black and a young woman. This never stops. And it is frustrating and exhausting.”

She continues, “I work in a healthcare system that continues to perpetuate harm in Black bodies and communities. As an OB/GYN, I carry the ugly and racist history of this specialty in our minds. I provide exceptional care and advocate for change, but I see the Black lives that are being harmed and/or lost. And this is scary, saddening, and sometimes feels hopeless.”

But even in the face of that weight, she finds power. “I also carry the hopes, dreams, strength, and resilience of all those who came before me. And all those who will come after me. We feel called to this work because we envision a better future. This is what keeps me going even on my worst days.”

Dr. Jones Pullins echoes this dual burden:

“We are often expected to be everything to everyone—expert, advocate, mentor, cultural translator, safe space, role model—while still navigating bias and systemic barriers ourselves. The emotional labor is invisible but constant.”

“The intellectual labor includes constantly proving your value, challenging norms, and building what doesn’t exist yet,” she adds. “We do it out of love, out of purpose—but we also need rest, recognition, and support.”

The words of Drs. Eryn Wanyonyi, Keri Garel, Maura Jones Pullins, and Joi Spaulding make one thing abundantly clear: Black Maternal Health Week isn’t just about medical care, it’s about justice.

Thier words remind us that we cannot address Black maternal health without addressing the full conditions that shape our lives like housing, access to food, environmental racism, economic insecurity, restrictive reproductive policy, and systemic medicalized violence. These are all reproductive justice issues. When we ignore those intersections, we fail our communities. When we treat Black maternal health as only a clinical issue, we overlook the structural violence that continues to harm Black birthing people. But the solution is already in motion: it’s in the doulas and midwives offering culturally rooted care. It’s in the organizers and policy advocates demanding Medicaid expansion. It’s in the physicians showing up fully for their patients and refusing to accept the status quo. It’s in the organizers building power, the elders passing down knowledge, and the young people refusing to settle for injustice.

To honor our healing legacies means believing that Black communities hold the solutions we need and resourcing that wisdom accordingly. It means centering the voices of Black birthing people, Black-led organizations, and Black women physicians. It means fighting for systems that make life—not just birth—possible.

Because until every Black birthing person has the safety, support, and sovereignty they deserve, our work is not done. And until we center the full humanity of our communities, there will be no justice.